Today I’d like to introduce a new library we’ve been working on - dataflows. DataFlows is a part of a larger conceptual framework for data processing.

We call it ‘Data Factory’ - an open framework for building and running lightweight data processing workflows quickly and easily. LAMP for data wrangling!

Most of you already know what Data Packages are. In short, it is a portable format for packaging different resources (tabular or otherwise) in a standard way that takes care of most interoperability problems (e.g. “what’s the character encoding of the file?” or “what is the data type for this column?” or “which date format are they using?”). It also provides rich and flexible metadata, which users can then use to understand what the data is about (take a look at frictionlessdata.io to learn more!).

Data Factory complements the Data Package concepts by adding dynamics to the mix.

While Data Packages are a great solution for describing data sets, these data sets are always static - located in one place. Data Factory is all about transforming Data Packages - modifying their data or meta-data and transmitting them from one location to another.

Data Factory defines standard interfaces for building processors - software modules for mutating a Data Package - and protocols for streaming the contents of a Data Package for efficient processing.

Philosophy and Goals

Data Factory is more pattern/convention than library.

An analogy is with web frameworks. Web frameworks were more about a core pattern plus a set of ready to use components than a library themselves. For example, python frameworks were built around WSGI e.g. Pylons, Flask etc. Or consider ExpressJS for Node.

In this sense these frameworks were about convention over configuration. They attempted to decrease the number of decisions that a developer using the framework is required to make without necessarily losing flexibility.

Like web frameworks, Data Factory uses convention over configuration with the aim of decreasing the number of decisions that a data developer is required to make without necessarily losing flexibility.

By following a standard scheme, developers are able to use a large and growing library of existing, reusable processors. This also increases readability and maintainability of data processing code.

Our focus is on:

- Small to medium sized data (KBs to GBs)

- Desktop wrangling - people who start on their desktop

- Easy transition from desktop to “cloud”

- Heterogeneous data sources

- Process using basic building blocks that are extensible

- Less technical audience

- Limited resources - limit on memory, CPU, etc.

What are we not?

- Big data processing and machine learning. e.g. if you want to wrangle TBs of data in a distributed setup or want to train a machine learning model with GBs of data, you probably don’t want this.

- Processing real-time event data.

- Technical know-how is needed: we aren’t a fancy ETL UI – you probably need a bit of technical sophistication

Architecture

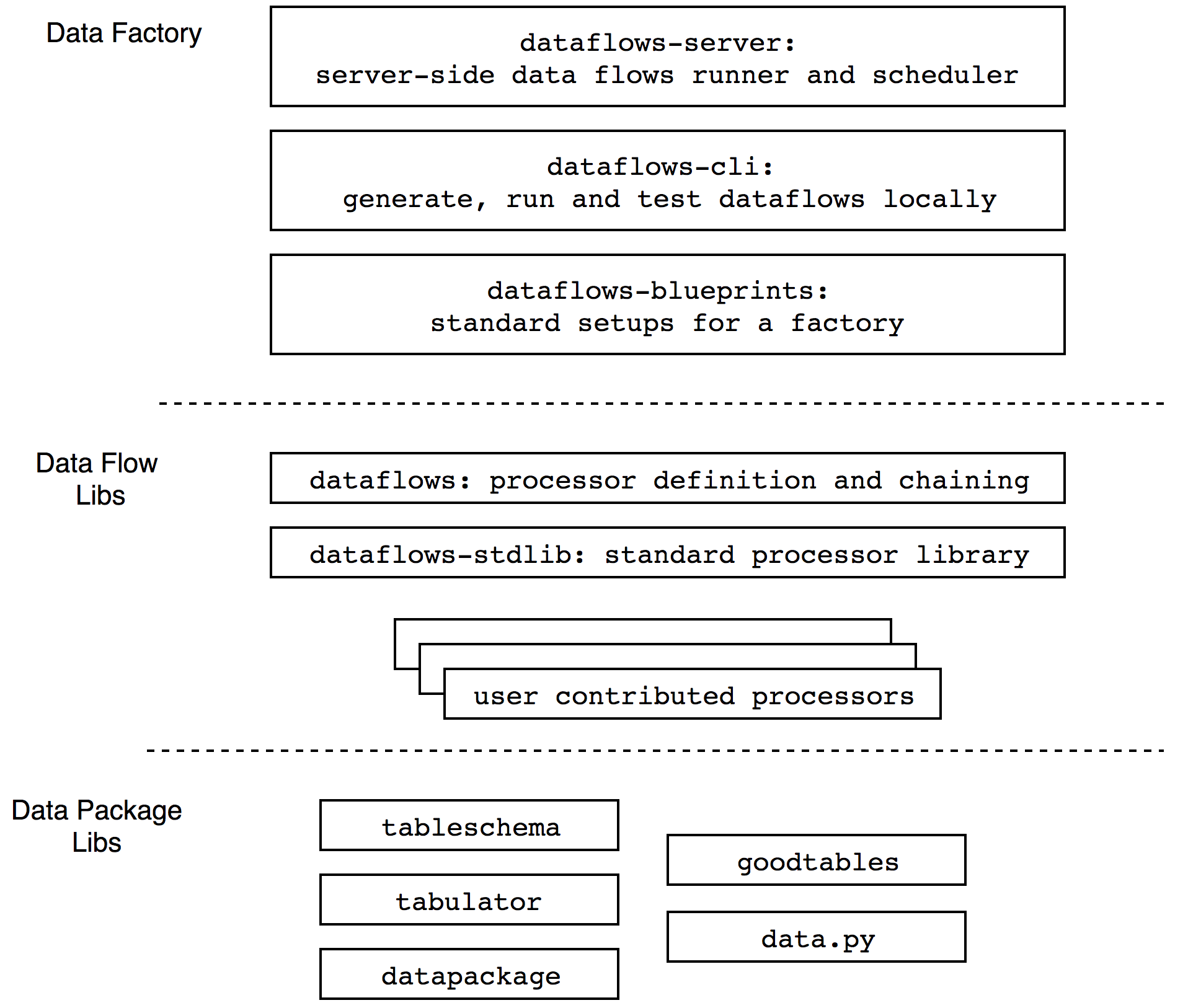

This new framework is built on the foundations of the Frictionless Data project - both conceptually as well as technically. This project provided us the definition of Data Packages and the software to read and write these packages.

On top of this Frictionless Data basis, we’re introducing a few new concepts:

- the Data Stream - essentially a Data Package in transit;

- the Data Processor, which manipulates a Data Package, receiving one Data Stream as its input and producing a new Data Stream as its output.

- A chain of Data Processors is what we call a Data Flow.

We will be providing a library of such processors: some for loading data from various sources, some for storing data in different locations, services or databases, and some for doing common manipulation and transformation on the processed data.

On top of all that we’re building a few integrated services:

-

dataflows-server(formerly known asdatapackage-pipelines) - a server side multi-processor runner for Data Flows. -

dataflows-cli- a client library for building and running Data Flows locally -

dataflows-blueprints- ready made flow generators for common scenarios (e.g. ‘I want to regularly pull all my analytics from these X services and dump them in a database’) - and more to come.

On Data Wrangling

In our experience, data processing starts simple - downloading and inspecting a CSV, deleting a column or a row. We wanted something that was as fast as the command line to get started but would also provide a solid basis as your pipeline grows. We also wanted something that provided some standardization and conventions over completely bespoke code.

With integration in mind, DataFlows comes with very little environmental requirements, and can be embedded in your existing data processing setup.

In short, DataFlows provides a simple, quick and easy-to-setup, and extensible way to build lightweight data processing pipelines.

Introducing dataflows

The first piece of software we’re introducing today is dataflows and its standard library of processors.

dataflows introduces the concept of a Flow - a chain of data processors, reading, transforming and modifying a stream of data and writing it to any location (or loading it to memory for further analysis).

dataflows also comes with a rich set of built-in data processors, ready to do most of the heavy-lifting you’ll need to reduce boilerplate code and increase your productivity.

A demo is worth a thousand words

Most data processing starts simple: getting a file and having a look.

With dataflows you can do this in a few seconds and you’ll have a solid basis for whatever you want to do next.

Bootstrapping a data processing script

$ pip install dataflows

$ dataflows init https://rawgit.com/datahq/demo/_/first.csv

Writing processing code into first_csv.py

Running first_csv.py

first:

# Name Composed DOB

(string) (string) (date)

--- ---------- ---------- ----------

1 George 22 1943-02-25

2 John 90 1940-10-09

3 Richard 2 1940-07-07

4 Paul 88 1942-06-18

5 Brian n/a 1934-09-19

Done!

dataflows init actually does 3 things:

- Analyzes the source file

- Creates a processing script for reading it

- Runs that script for you

In our case, a script named first_csv.py was created - here’s what it contains:

# ...

def first_csv():

flow = Flow(

# Load inputs

load('https://rawgit.com/datahq/demo/_/first.csv',

format='csv', ),

# Process them (if necessary)

# Save the results

add_metadata(name='first_csv', title='first.csv'),

printer(),

)

flow.process()

if __name__ == '__main__':

first_csv()

The flow variable contains the chain of processing steps (i.e. the processors). In this simple flow, load loads the source data, add_metadata modifies the file’s metadata and printer outputs the contents to the standard output.

You can run this script again at any time, and it will re-run the processing flow:

$ python first_csv.py

first:

# Name Composed DOB

(string) (string) (date)

--- ---------- ---------- ----------

1 George 22 1943-02-25

...

This is all very nice, but now it’s time for some real data wrangling. By editing the processing script it’s possible to add more functionality to the flow - dataflows provides a simple, solid basis for building up your pipeline quickly, reliably and repeatedly.

Fixing some bad data

Let’s start by getting rid of that annoying n/a in the last line of the data.

We edit first_csv.py and add to the flow two more steps:

def removeNA(row):

row['Composed'] = row['Composed'].replace('n/a', '')

f = Flow(

load('https://rawgit.com/datahq/demo/_/first.csv'),

# added here custom processing:

removeNa,

# now parse column as Integer:

set_type('Composed', type='integer'),

printer()

)

removeNa is a simple function which modifies each row it sees, replacing n/as with the empty string. After it we call set_type, which declares the Composedcolumn should be an integer - and verifies it’s indeed an integer while processing data.

Writing the cleaned data

Finally, let’s write the output to a file using the dump_to_path processor:

def removeNA(row):

row['Composed'] = row['Composed'].replace('n/a', '')

f = Flow(

load('https://rawgit.com/datahq/demo/_/first.csv'),

add_metadata(

name='beatles_infoz',

title='Beatle Member Information',

),

removeNa,

set_type('Composed', type='integer'),

dump_to_path('first_csv/')

)

Now, we re-run our modified processing script…

$ python first_csv.py

...

we get a valid Data Package which we can use…

$ tree

├── first_csv

│ ├── datapackage.json

│ └── first.csv

which contains a normalized and cleaned-up CSV file…

$ head out/out.csv

Name,Composed,DOB

George,22,1943-02-25

John,90,1940-10-09

Richard,2,1940-07-07

Paul,88,1942-06-18

Brian,,1934-09-19

datapackage.json, a JSON file containing the package’s metadata…

$ cat first_csv/datapackage.json # Edited for brevity

{

"count_of_rows": 5,

"name": "beatles_infoz",

"title": "Beatle Member Information",

"resources": [

{

"name": "first",

"path": "first.csv",

"schema": {

"fields": [

{"name": "Name", "type": "string"},

{"name": "Composed", "type": "integer"},

{"name": "DOB", "type": "date"}

]

}

}

]

}

and is very simple to use in Python (or JS, Ruby, PHP and many other programming languages) -

$ python

>>> from datapackage import Package

>>> p = Package('first_csv/datapackage.json')

>>> list(p.resources[0].iter())

[['George', 22, datetime.date(1943, 2, 25)],

['John', 90, datetime.date(1940, 10, 9)],

['Richard', 2, datetime.date(1940, 7, 7)],

['Paul', 88, datetime.date(1942, 6, 18)],

['Brian', None, datetime.date(1934, 9, 19)]]

>>>

More ….

Lots, lots more - there is a whole suite of processors built in plus you can quickly add your own with a few lines of python code.

Dig in at the project’s GitHub Page or continue reading the in-depth tutorial here.

We make tools, apps and insights using

open stuff

We make tools, apps and insights using

open stuff

Comments